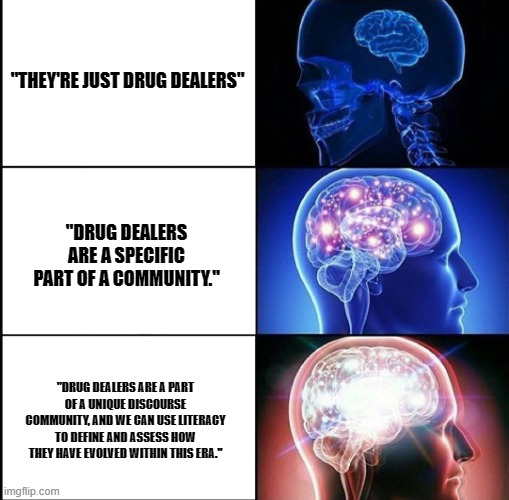

Now that I have your attention, I must share some unfortunate news. No, this is not some weird Vice article. As a twenty-one-year-old suburban woman who still occasionally worries about getting carded at Applebee’s, I am certainly not an expert when it comes to selling drugs.

You know who would most likely have this skill? A drug dealer. This is because a drug dealer has acquired a certain literacy about the world of drug dealing.

When most people think of literacy, they think of reading and writing, or what they were taught in school. Literacy is greater than that. It is about understanding a subject or area. Reading and writing are just a few of the applications that can help one assess their level of understanding of an area.

Through this view of literacy, we may find that a drug dealer has various literacies, such as testing a drug’s quality or knowing certain drug laws in their state.

Literacies affect our everyday life. Mutual competencies can bring people together. Understanding the complexity of literacy provides a different lens that reshapes how you look at everyone in your life – even the clerk at your local dispensary.

A Drug Dealer’s Discourse

Everyone has an identity complete with a variety of factors that make up that unique identity. Shared identities often come together to make a group revolved around their commonalities. Retired linguist James Gee defines this concept, called “discourse”, in length in his work “Literacy, Discourse and Linguistics: Introduction”. According to Gee, discourse is a social “identity kit” that provides instructions on “how to act, talk and often write, so as to take on a particular role that others will recognize”. Discourses are often not taught formally; rather, they are taught through social situations that will indoctrinate someone into a certain discourse community.

Gee also breaks down discourse into two main categories. Primary discourse consists of our very first social interactions at the home. Secondary discourse is made up of social interactions at institutions that are outside of home, such as school or a club. Gee further compartmentalizes secondary discourses into two more categories. Dominant discourse, when mastered, brings about positive gain of social “goods”, such as money or prestige. Nondominant discourse mastery is only great for solidarity in a community.

For the most part, drug dealers learn their trade as a secondary discourse. Whether it is a dominant or nondominant discourse is up to how socially profitable their business has become.

From Rapper to Crack Dealer

Often, there are groups that have similarities to each other but are still distinct. One might jump from one group to another group, thinking it would be a seamless transition. However, this is not always the case.

One example that comes to mind comes from a scene in 2005 Adult Swim television series The Boondocks. In this scene, Thugnificent, a rapper who is in deep financial trouble with the IRS, decides to sell crack to pay off his dues after listening to a rap song that goes into detail about how to make the drug. Thugnificent seems to make good progress at first, successfully finding two interested customers. However, when he is spotted by one of his fans, everything falls apart. He leaves his second customer hanging in the process of selling to get rid of the fan who spots him. The first customer comes back to try to get a refund on his burnt crack. Frustrated, Thugnificent runs away.

As hilarious as this scene is, it provides a great depiction of the type of conflict that can occur between discourse communities. Thugnificent belongs to a discourse community of rappers. He tries to enter the world of drug dealing, thinking it would be simple, because of the seemingly shared overlap between the two communities, as seen through common associations of rap music and drugs. Although his language was appropriate for an urban drug dealer, his inexperience shows through his actions, such as making burnt crack and not knowing how to conduct a smooth drug deal. Despite his attempt and assumptions, Thugnificent does not fit into the drug dealer community.

The Digitally-Competent Drug Dealer

Understanding Literacy in the Digital Age

Earlier, we discussed how literacy is a level of competency in a subject area that is far beyond reading and writing. Gail Hawisher and Cindy Selfe delve into the concept of literacy further by looking at how it has evolved through the technological age.

In “Becoming Literate in the Information Age”, Hawisher and Selfe describe how literacies have life spans. Often, people have to simultaneously grapple learning and valuing past and present forms of literacy to become, in a way, “up-to-date” with what is expected by society. Hawisher and Selfe assessed two women, Melissa and Brittany, and their technological competencies. Melissa, born in the 1960s, rarely had access to computers growing up. She had to learn to adapt to modern technology well into adulthood. Brittany, on the other hand, was born in the 1980s, and had more regular access to computers and other technology than Melissa. Despite just a twenty-year difference, these two women obtained different cultural technological competencies at varying levels that shaped their digital literacies.

Generations of Hitting Up the Plug

When it comes to drug dealing, the advent of advanced technology has built a digital literacy has transformed the community. Journalist Paulie Doyle’s “How Mobile Phones Changed Drug Dealing” analyzes this transformation. Before the late 1990s, a former drug user known as Jason details how drug dealing was more so “seen as being part of a community”. People were trying to keep up with their own habit and sharing with others rather than pushing whatever they were selling. They formed trusted relationships with their sellers. You would have to find discreet, specific places that would slip you whatever you wanted. Most of all, if your dealer could not supply for whatever reason, you were stuck.

After the late 1990s, with the rise in smartphones, the drug landscape changed vastly. 24/7 service became available. However, it came at the cost of being less discreet. Coded language for drugs slowly died out, with dealers having much less fear of getting caught than ever before. This is due to the normalization of drug use; police are not arresting people as much for petty drug-related crimes. People eventually ditched the old-school dealer for someone who can be contacted with a number or username. If the old-school dealer could not quickly adapt to this new literacy, they would lose out on business.

. . .

It is crazy to think of how drug dealing could be looked at in a scholarly way. That just speaks to the power of understanding literacy and the discourse it creates. Since I cannot “unsee” all of this after learning this much about it, you cannot either. You’re welcome.

Leave a Reply